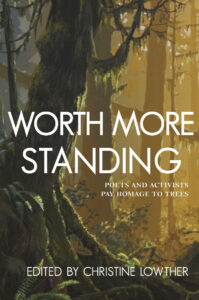

Followers of environmental news will know of the ongoing protests over old growth logging at Fairy Creek, southwest Vancouver Island. In tune with this, Christine Lowther named the substantial anthology she’s edited for Caitlin Press Worth More Standing.

Followers of environmental news will know of the ongoing protests over old growth logging at Fairy Creek, southwest Vancouver Island. In tune with this, Christine Lowther named the substantial anthology she’s edited for Caitlin Press Worth More Standing.

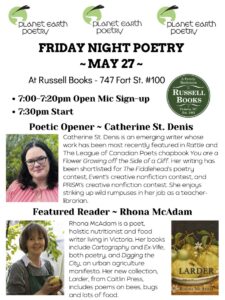

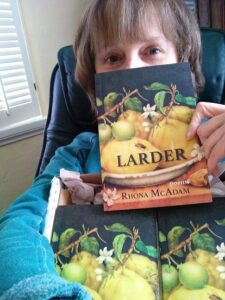

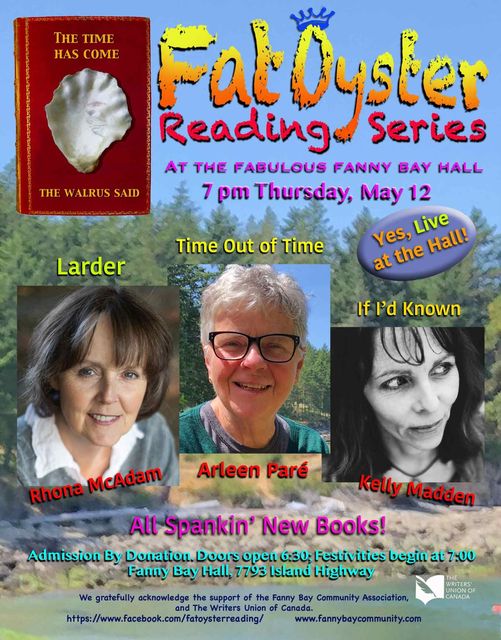

Clocking in at 239 pages, the anthology is a veritable forest of Canadian poets paying homage to trees of all kinds. I am one who contributed two poems to this work, including a poem from Larder.

On Saturday May 28 I will join five other poets at the Harbourfront Library in Nanaimo to help launch this with a live, in-person reading.

Poets who will be reading at the Nanaimo launch include: Leanne McIntosh, Ann Graham Walker. Rhona McAdam, Nicole Moen, Sheena Robinson and Kim Goldberg.

The reading runs from 1-3pm and is free and open to all.