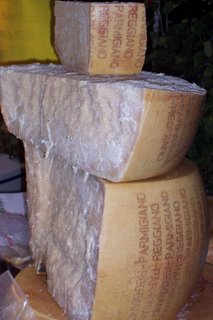

Hmm… what’s wrong with this picture…

Enjoying the walk back to class. Postprandial view: fountain at the Reggia di Colorno.

Week two has started at the University of Gastronomic Sciences, and we’re deep into microbiology and the technology of cheese. A classmate has thrown down the gauntlet and invited me to find poetry in that.. but first I must master the terminology. No easy thing. But perhaps by the end of the week I’ll know my triglycerides from my diglycerides and my casein from my hydrolytic enzymes. Yessir… thank the lords ‘n ladies of technology for Wikipedia is all I can say. And bless the foresight and generosity of Douglas Goff for creating the Dairy Science and Technology website.

And thank heavens for email. One of my correspondents reliably informs me that at the moment a company in the UK is being hauled over the coals for calling their product “Welsh Dragon Sausages” on the grounds that it is not a true description of the contents. Apparently a commentator on this topic noted that it had blown the cold wind of fear into the makers of shepherd’s pie, angel cakes and chocolate brownies.

Owing to my continuing throat ailment I stayed in tonight and had some nourishing soup. Not chicken soup which I’m sure really does cure everything, but some rocket soup, a kind of vegetable jet fuel I’m hoping, and nice to eat while you catch up on the story of Elizabeth Smart and George Barker:

Rocket Soup

1 tbsp butter

1 large shallot, minced

1/4 cup minced fresh fennel

1 small carrot, minced

1 medium potato, diced

3 cups vegetable broth

2 cups rocket

- Melt the butter in a saucepan on medium and add the shallot, cooking for a couple of minutes until soft.

- Add the fennel and carrot and cook gently on low heat about 10 minutes.

- Add the potato and then the broth. Bring to the boil and then simmer another 5-10 minutes until the vegetables are soft.

- Add the rocket, cover and cook another few minutes until the rocket has wilted. Season with salt and pepper.

- I was lacking a blender, but it could (should?) be blended/pureed at this point or served as is.