We began our Tuesday last week in a room at Garofoli Winery, with a talk by Dott. Antonio Attorre (President of Slow Food Marche and teacher at the Università Politecnica delle Marche) about Le Marche as a food-producing region, which is largely a story about landscape. While – as we’d previously learned – Italy is 80% mountains, which affects everything about the country; this region has 13 rivers, which means 13 valleys and 13 different food traditions. It is further divided into mountain-dwellers and a coastal population, and still shows the pattern of the feudal system that marked it in previous centuries: houses are surrounded by a small piece of land, so it is not a system of intensive farming, but a more fragmented patchwork of vines and olive groves.

We’d heard at some length the afternoon before (during a talk on a Presidia product, the Portonovo “mosciolo” / wild mussel) that in coastal areas, the farmers who worked land in the hills also often doubled as fishermen, in order to supplement their diet and income with seafood. So, we were told, somewhat unique in Italian cuisine is Le Marche’s preference for dishes that combine vegetables with seafood. (To be honest, we didn’t notice many vegetables in the food we ate last week, but we had been noticing, in Parma, the segregation of vegetables and meats which are, where both occur in a meal, often served in different courses.) He also mentioned that the seafood recipes of the region have an obvious historical link with local meat-based cuisine, since the techniques for cooking fish often mirror those for meat – you simply substitute the protein source.

Le Marche, he said, was the first region in Italy to embrace organics, and ten years ago began organic trials. It also pioneered beef certification (for traceability, post-BSE), and seven years ago was able to win EU exemptions for small scale cheese producers who had been crippled by regulations designed for large scale operations. He mentioned A.S.S.A.M., l’Agenzia Servizi Settore Agroalimentare Marche, which provides research and advice for the region’s agricultural industries.

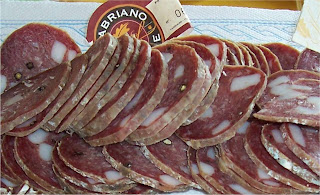

Next we had a talk about and lunched on three Le Marche Presidia products: the Mele Rosa dei Monti Sibillini (a sweet, long-lasting heritage apple, mountain-grown, brought back from the brink of extinction); Salame di Fabriano (a seasonal, hand-cut salami, with cubes of lard and whole peppercorns, made from prime prosciutto-grade pork); and Pecorino dei Monte Sibillini (pecorino fresco, a young, soft version of the sheep’s milk cheese we’ve been happily encountering at every turn).

Over the lingering lunch hour we took a side trip – thankfully at the wise and persistent urging of our art history grad Fabi – to see the Basilica del Santuario di Loreto, a stunning basilica built around the shrine of Santa Casa Maria (the Virgin Mary’s house, in which the Enunciation is said to have taken place). It had been, so they say, spirited away from Nazareth by the angels, and arrived here via Croatia in the fourteenth century. It was encapsulated in the basilica in 1507 and has been visited by pilgrims ever since.

We returned to Garofoli for a talk and tasting to embrace the region’s long wine-making tradition, dating back to those early vinificators, the Etruscans, who took a turn of influence here.

Started as a family enterprise in 1871, it is run today by the brothers Gianfranco and Carlo. Carlo is the enologist, and he gave us a short history of the region’s wines, and the transition of Italian wines from the 1950s through the present. We had been hearing a lot about Verdicchio, and he explained its status as the first DOC wine of the area.

Some sources, he said, claim it has been grown in Le Marche for 2000 years, but he would be willing to bet on the past 150 for sure. This varietal grows well in the area, usually within 20 km of the sea, favouring the mild climate and sandier soil, but is susceptible to diseases, especially moulds, and matures quite late. While exposure and altitude affect the alcohol content and acidity of wines, the interesting piece of trivia he shared about Verdicchio grapes is that the river Esino, which empties into the Adriatic north of Ancona, separates production areas into yields of higher and lower acidity.

Verdicchio began as a strong, high-alcohol wine, but has been refined into a fruitier, milder wine with a lower alcohol content. I think he was saying this was a result of American tastes for such wines, and is also the product of Italian wine-making efforts over the past thirty years to stabilise the quality of wines, while retaining their individual characteristics.

He talked about his growing methods, which we’d learned a bit about in our wine history classes. He said that previously they’d used four vines per plant but discovered that using only one would give more light to the plant, make it hardier and healthier, and therefore give a more reliable yield with less need for fertiliser. And then we tasted some wines (a couple of Verdicchios: Podium and Serra Fiorese, and a red from the other big Le Marche grape, Montepulciano: Grosso Agontano) after which we rampaged through the shop and then had a free supper. Which we enjoyed very much at Trattoria La Rocca, where – after running amok in the enoteca next door – we dined on fresh anchovies, fried sardines, crab pasta, battered wee fish and a lovely, lovely salad. And a sort of creamy lemon slurpee for dessert, followed by a very potent ‘fisherman’s coffee’ and a pleasant amble back to the hotel along the tree-lined sea front.