So little time, so many food heroes. I was thrilled to bits to hear from so many speakers whose books I’ve read or whose words I’ve heard on film or from others.

Terra Madre offered lots of opportunities to hear and exchange information, in Earth Workshops within the event itself, only open to delegates, or at Terra Madre conferences in the Salone del Gusto, where the public could sit in and hear from truly memorable speakers.

The only difficulty – as you might expect from such a ferociously huge and busy few days (those words spectacularly understate the scale of what went on) – was splitting yourself into enough pieces to make it to a fraction of what was on offer. Here is a sliver of a tiny wedge of what I was fortunate enough to catch.

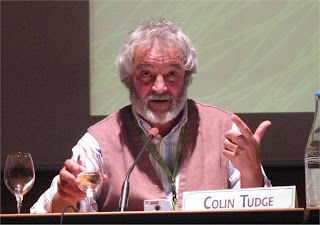

The wonderful Colin Tudge, whose latest book (Feeding People is Easy) is being translated into Italian and will be published by Slow Food Editore this year, promotes the principle that feeding people is easy– if you design your agricultural systems to feed people instead of produce commodity crops for export. He covered similar ground and explained why our agricultural systems have evolved into such a shambles in his earlier book, the charmingly titled So Shall We Reap (Socially Reap? asked a young person I mentioned it to– perhaps not totally up on those biblical references..)

Luca Mercalli, clearly a graduate of the Al Gore Climate Project training enterprise, spoke well about the repercussions of climate change on food production, and particularly about the issues around water which will affect us all. He mentioned the water shortages which will result from the ongoing global population increase and urbanisation; the effects of covering the earth with concrete; the effect of water on the climactic balance of the earth; and the rise in sea levels that will rob large parts of the earth of fresh drinking water. He cited in particular the IPCC paper on Climate Change and Water.

A word from Cuba… or rather a few hard words from economist Osvaldo Martinez, president of the Economics Commission of the government of Cuba, about the roots of recent food price increases,which he felt were not linked to a collapse in food production, but to financial speculation. He raised some serious questions about the morality of commodities trading in a world where hunger still exists.

What must now be questioned, he said, was the idea that the financial market can solve everything in the best way and so had to be left free without interference or adequate regulation. What we see in the current financial crisis results from the progressive abandonment of policies set up after lessons learned in the depression of the 1930s. He stressed the importance of separating real from financial economics: whereas real economies create goods to meet real human needs, financial capital is devoted to speculation and managed in a virtual economy.

Unfortunately for all of us, devaluation of the virtual economy has had real effects on economic activity, leading to actual loss and ruin by real people.

Awesome: Oxfam Spain’s Ariane Arpa walked through a range of causes of the food crisis, which prefigured the financial crisis, and addressed a number of critical issues to do with the global food supply. Financial speculation was certainly there, she agreed, but it wasn’t the whole cause. There was a global drop in food production due to drought (e.g. in Australia) and to climate-related problems, such as finding water in Africa: as the water disappears, people are forced to move away and agricultural production stops until – and more importantly if – they resettle elsewhere. There has been an increased demand for commodity crops (wheat, corn, soya etc.) in emerging countries such as China and India, but this increase has been gradual, so isn’t the main cause either. The demand for biofuels and the commensurate reduction of arable land available for food production has had its impact. And of course the spike in fuel prices crippled those whose food budget was already stretched to breaking point.

Her concerns also addressed many of the issues covered in Oxfam’s Agriculture campaign. She mentioned the failings of development models of the past 30 years, which were based on the systematic destruction of small farming, and the resulting lack of self-sufficiency on the part of aid-seeking countries. Our foreign aid policies have not invested in farming that could feed the populations, and we – or worse, they – are now and suddenly paying the price.

And what a price: we complain because our food expenditures are rising from an average of 10-15% of our income or so in the West; consider how families in Somalia spending 70-80% of their income on food will cope with a 4 times increase in the cost of wheat. A family with that kind of personal financial crisis can’t afford to pay for healthcare or the education of its children, particularly girls; they will have to reduce the number of meals they eat from two to one. In Haiti she had seen people eating pastries made of mud, because they fooled the stomach into thinking it had had food.

In a world where more than half the world’s population now lives in cities, people have no choice but to buy food at markets, and pay market price whether they can afford it or not. Millions of farmers farm land they do not, cannot ever afford to own.

But have the food and financial crises created opportunities for small producers to make money from higher prices? Unfortunately not; Oxfam studied 30 countries and found that small producers are in the same fix as other consumers: they may produce food, but they also have to buy what they can’t grow, at market prices. They lack the financial weight to influence the price of food, which is fixed by intermediaries. The winners are always the same: huge food companies; among many others, Tesco and Carrefour have reported large gains this year.

So it’s a political problem and one that needs a political solution. The development model has to be changed to increase support to agriculture and to small producers, who are most often found in undeveloped parts of the world. In short, she said, we need change that will make it impossible to sell an imported frozen chicken for less than a locally reared one.

Ethiopa speaks: Tewolde Berhan Gebre-Egziabher talked about globalisation, and the evils of the unnecessary movement of food from one part of the world to another, exacerbating climate change and driving people off their land. Industrial agriculture, he said, in its market-oriented nature rejects any ecological intervention because it must keep focused on its obligations to the market. It hastens the destruction of soil productivity beyond any other method. With industrial chemical inputs and reduction of plant species (monocultures) it seeks to raise production levels beyond sustainable limits: it is inherently destructive of any kind of natural environment. Traditional methods such as crop rotation and mixed farming incorporate practices such as manuring to enhance soil health, but industrial methods of food production require separation of plants and animals. He concluded by saying he was ashamed to come from Africa, the cradle of humanity, if humanity was so bent on destroying the earth that sustained it.

The fabulous Vandana Shiva, simple and powerful eloquence in one commanding package. She spoke about the effects of the green revolution on agriculture in India: all that this seeks to increase, she said, are a few commodities. Its weakness is that it lacks balance in foods that it promotes, in favour of monocultures, and of chemical-based farming which prohibits biodiversity. Green revolution food output per capita is lower per acre than that of traditional methods.

Monoculture agriculture depletes the soil, but it also creates financial problems for farmers. If farmers expend a lot of money on seed and chemicals, they must sell everything to pay off the debt. (Where this is not enough, the results, farmer suicides, have been well documented for many years. I can’t think of too many deaths worse than drinking pesticide…) The answer, if farmers are getting into debt with high cost inputs, is to establish agriculture with low cost inputs: ecological farming. The countryside needs to be repopulated; remove the fossil fuels and machinery and there will be room for people.

Shiva’s real ire is directed at biotech’s theft of a farmer’s basic human right to save seed. Monsanto has turned this into a crime, and worse: a business opportunity. Her answer has been to establish seed banks where farmers can save climate resilient seeds. Genetic modification is, she says, too crude a technology to do this, but instead seeks to map and patent the genetics of seeds and through genomics, expecting the world to pay royalties.

Another wrong she named was that sellers of agricultural inputs are also buyers of commodities: this is the only industry where this happens, and it taints the whole cycle. When sellers of chemicals and seeds are also wanting to buy food cheap, this traps third world economies in debt. Globalisation has created, says Shiva, a massive scam, which robs farmers through low prices. Thus in these intersecting circles, the poor are financing the rich, the farmers are financing the cities.

Food production is the only area of production where the more you process, in search of higher profit margins, the less you get: the less food becomes food.